Analog vs Digital Recording: The Question

Few topics create as much debate as to the talk of Analog vs Digital recording. Without digital technology, the world is a very different place. We wouldn’t have a computer, laptop, tablet, or smartphone. Even the music you record wouldn’t sound the same. The music you love to listen to is different as well.

Digital Recording

Digital recording is sometimes criticized for sounding harsh. It is described that way because it is clean. It is lacking the analog harmonic distortion.

Analog vs. Digital war. But wait – can’t you record digitally, and then add those pleasing harmonics with a plug-in? Not so fast. If you want the best of both worlds, you have to use the right tool: a digital-analog hybrid recording system.

An analog summing matrix, when combined with high-quality microphone preamps and converters, is the best way to use the speed, convenience, and pristine sound of digital. Its features combine with the unmistakable warmth of analog, creating what I like to call “the mixing board of the future.”

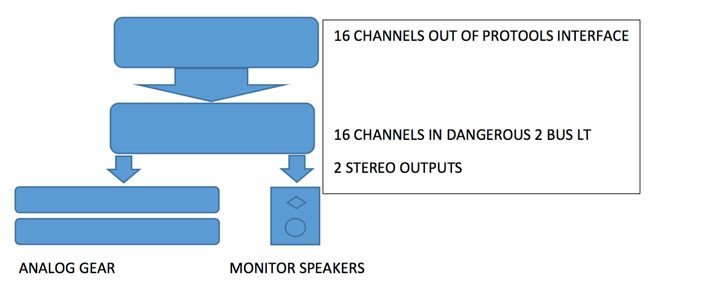

Here’s an example: Combine instruments of like design, drums, guitars, bass, keyboards, vocals, background vocals, and effects, and bus them to 16 outputs of your DAW. Connect those outputs to the 16 inputs of the analog summing matrix. This matrix will feed 2 identical stereo outputs that are the summed result of the inputs. Come again? Look at this way: a mixing board has many channels, all of which are sent to the primary left and right outputs, allowing an audience to hear you at a gig. But there are other stereo outputs of that same signal. The headphone output is one example.

Analog Summing

Analog summing works on the same principle. All of the inputs are routed to a stereo output (of which there are two). Since the same signal comes out of both stereo outputs, one can be sent directly to your monitoring system for a reference.

The other, and this is where it gets exciting, can be sent to your analog gear. This allows you to fatten up the sound with harmonic distortion and other effects. You also have to keep an ear on how it interacts with and affects your mix. Keep in mind that your reference signal will also be slightly affected by the analog summing process – see the diagram below:

The Tricky Part

The Analog vs Digital war is not over. Here’s where things get a bit more complicated but bear with me. To get the analog signal back into your DAW, choose an AUX input and an audio input, and route the analog stereo signal path back into your digital audio workstation with the AUX bussed to the audio channel. My setup consists of Pro Tools HD, the Dangerous Music 2 Bus LT (the summing matrix), and the Dangerous Music Monitor ST (a monitor controller).

One of the two stereo signals goes from the 2 Bus LT directly into the Music Monitor ST, providing the reference. The second stereo signal gets routed from the 2 Bus LT to my analog gear, including stereo pairs of the Rupert Neve 542 (a transformer-based, voltage-responsive tape saturation emulator, superior to software emulations), 543 (a warm-sounding compressor-limiter) and 551 (a musical- sounding 3-band EQ).

The Analog Signal

The analog signal is routed back into Pro Tools, to an AUX track. The reason that I use an Aux track is simple: with that stereo return instantiated, it is possible to add plug-ins to the chain. If an audio track is used, you cannot. The AUX track then gets bussed to an audio track, and printed or recorded as the master.

Using Pro Tools, it’s possible to hardwire analog gear to an interface, and use the outboard gear as a plug-in – and it’s already delay-compensated, eliminating latency issues. In the I/O setup of Pro Tools, you can route this on the insert page. Just imagine analog equipment as a plug-in! You could use an outboard sub-harmonic EQ on a bass line or your favorite compressor on a vocal track. Then, still use a software plug-in instantiated after it for further processing. How awesome is that?

Outboard gear is terrific – and often expensive. A high-end analog mixing board and 16 track, 2” tape machine can be had, but for a king’s ransom. That is before the inevitable maintenance costs. For example, a Rupert Neve 5088 16 channel large format console would run you over $71,000. A fully restored and aligned Mara Machines 16 track, 2” tape machine would set you back another $10,000. We’re talking over $80,000 for two pieces of gear, and that gives you only 16 channels.

By Comparison Here Is My Setup

• Pro Tools HD

• Three interfaces 40 input channels total. (2 HD I/O’s and 1 HD Omni)

• Three Audient ASP 800 Preamps - 24 channels total.

• Six Rupert Neve analog 500 modules (stereo pairs of the 542, 543 and 55) • Four Elysia 500 modules

• Dangerous Music summing matrix and monitor controller

The above costs less than 1/4 of a 16 channel analog mixing console and 2” tape machine.

Analog vs Digital. Is the warm sound of an all-analog recording system (with its characteristic yet unpredictable behavior), worth over four times the cost of an analog-digital hybrid system? Perhaps – to the patient, deep-pocketed traditionalist. As for me, well, I’ll let my hybrid system speak for itself. I hope you’ve reached the same conclusion I have: that there’s nothing “wrong” with digital recording. That is, its flexibility makes it possible to incorporate the warm, magical qualities of a tape-based analog system, but with far more reliability, repeatability – and at a fraction of the price.

The future is here. The Analog vs Digital war is over for now. Stay tuned for more. Happy mixing!